Wage growth across Central Europe has sped up to 5-10%, closing the gap again with Western peers.

Cheap and skilled labor has been one of the reasons CEE banks are so cost efficient and profitable.

Could fast growth in wages endangers superior profitability of CEE banking?

In 1991, the average Czech was paid only 6% of the salary earned by his German counterpart. In absolute terms, this is was only USD 129 a month. Some two decades later, the salary has increased to over USD 1,400, or 35% of the German level, as CEE economies have succesfully transformed into market economies and become a part of the EU.

The financial and economic crisis alongside the Czech Central Bank trying to weaken the local currency reversed that convergence for a few years. Czech gross wages dropped to USD 1,110 a month and to 32% of the German level in 2016. That's in spite of the fact that the average nominal wage growth remained at 2-3% a year in 2011-2016.

The situation changed significantly in 2017 as nominal wage growth sped up to over 5% and CEE currencies started appreciating again. With an average wage of approximately USD 1,500 a month, or 37% of the German level in 2018, the highest ever, pressure is rising! As unemployment has dropped to an all-time low, personnel costs and the difficulty of finding the right people has started giving many companies a major headache in remaining competitive:

Banks are certainly in the front line here. Their personnel cost usually forms 40-50% of overall operating costs, so they will be among the first to feel the pain. Relatively cheap and skilled labour has always been one of the attractions for investing into the region, as seen in high FDIs into manufacturing in the 1990s and increasingly into services in the last decade or so. When looking at the bank's financials, it was also one of the reasons CEE banks are some of the most cost efficient globally with cost to income at below 50%.

In spite of the significant relative growth in average wages, Central Europeans are still paid far less than their western-European peers. In 2017, the average Czech made USD 1,276 gross a month, Hungarians earned USD 1,035 and the average Pole grossed USD 1,104 per month. That's compared to USD 4-5,000 for their western counterparts:

With bankers making usually 2-3 times more than the rest of the people in the economy, the difference between Central and Western-European bankers can be even bigger, as much as USD 5-6,000 in absolute terms a month:

The difference is nicely seen when comparing salaries of western-european banks with their CEE subsidiaries. While the average cost per employee amounted to approximately EUR 7,000 per month in Austria in 2017 (that's including health and social security expenditure), Czech bankers would have cost some EUR 2-3,000 only.

The comparison between Erste Bank's Sparkassen personnel costs in Austria and some of Erste Bank's subsidiaries further south-east such as in Serbia, or Romania demonstrates the difference pretty conclusively:

To be fair, low salaries mean nothing on their own, as we have seen in a number of countries with a disfunctional banking system. The conquest of Central European banking by banks such as Austria's Erste Bank and Raiffeisen Bank, Belgium's KBC or France's Societe Generale has been clearly beneficial for both sides. Most Central Europe countries now have a stable, efficient and profitable banking system, which could be difficult to imagine without the presence of foreign banks and their knowhow.

At the end of 1990s, Czech banking was virtually bankrupt. Bad loans represented a third of total loans as lending had been politically motivated. Banks had to be recapitalized to fulfil capital requirements and the Government had to issue further guarantees to attract sellers when privatizing its banks.

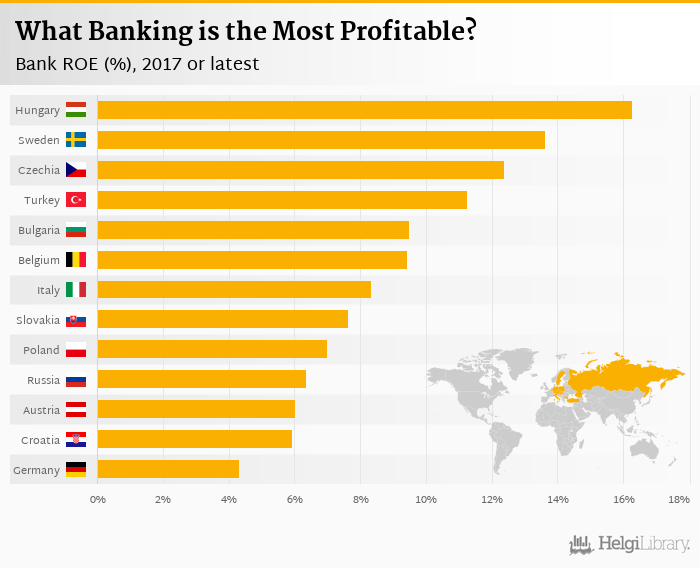

Only 10 years after privatization, Czech banking has created an impressive picture. For the last decade or so, banks' return on equity has approached 10-15%, cost to income is well below 50% and capital adequacy is sniffing at the feet of 20%. A picture comparable truly to the best banking systems in the west, such as Sweden for example.

A number of other countries in Central and South Eastern Europe have been showing a similar picture in the last years, as economic growth picked up after the crisis:

So, could the unprecedented pressure on wage growth in Central Europe endanger the profitability of their banks?

Yes and No...

The impressive profitability improvement of CEE banks in the last two decades is the result of a number of structural factors (privatization, arrival of foreign owners and restructuring) and an impressive economic growth in the region.

Households have become richer and more leveraged. In the 1990s, mortgage loans practically didn't exist. In 2018, however, every fifth household held a mortgage. Mortgage loans now represent more than 20% of GDP in the most developed countries such as the Baltics, the Czech Republic, or Poland which fuelled a lot of extra revenue and asset growth in the last decade.

Although overall penetration of financial services remains well below the western-european level, this growth must and surely will slow down.

This will be a challenge for banks in particular. Some banks are not waiting for the tide to turn and have already started cutting their numbers and changing their structure more in favor of the front-office staff as technological innovation brings cost savings.

So, to sum up, the jury is still out here. The pressure is clearly rising, so a deterioration in profit is likely to be seen within the sector. On the other hand, banks still have some weapons to fight the trend through volume growth, higher interest margins on the back of rising rates, or technological innovation. The coming years could therefore show which bank read the upcoming trends better than the rest...

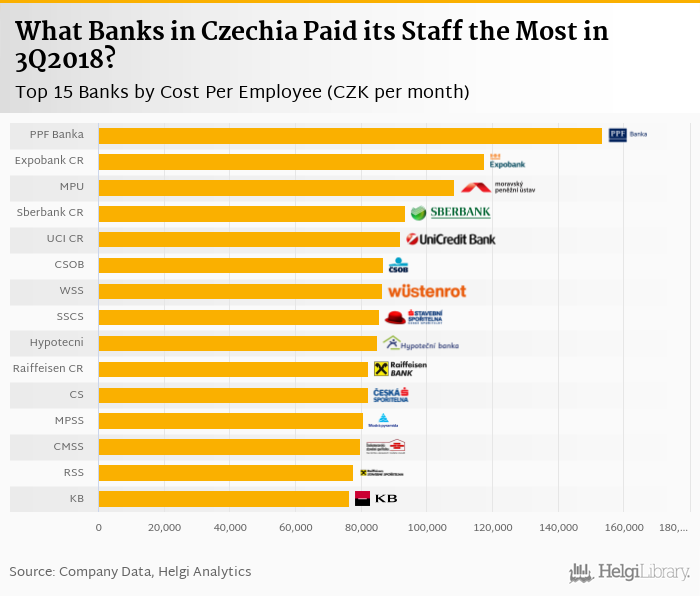

Cost of bankers varies dramatically between banks within a single country. Investment and corporate bankers are usually better paid than employees of retail banks, for example:

You can see all the banks cost per employee data at Cost Per Employee indicator page.